It Turns Out Part of Road-Tripping is Playing Hundreds of Board Games

This trip had a lot of themes: visiting national parks, catching up with friends I hadn’t seen in years, seeing mountains of all sorts, and of course, seeing The West one last time before I get an apartment in the eastest part of the East Coast and settle into the bubbliest part of the liberal bubble ecology. But another theme, unexpectedly to me but quite predictably to probably anyone, is that we have played a shitton of board games. We went to actual board game cafés in Portland and Denver (of course), and found ways to play quite a few other games at various times. Below is a sampling of some of the games we’ve discovered or rediscovered on this trip.

Star Realms (Colony)

Gameplay: Star Realms is a deck-building game with Trade ($), Combat, and Authority (health). You start with eight Scouts that give you one Trade each, two Vipers that provide one Combat, and from there you simply buy cards from the main deck, working your way up to ever more powerful Ships and Bases. You win by reducing your opponent’s Authority to 0 before they get you.

Review: This is one of the most pleasantly complicated games I have ever played. There are four factions—Trade Federation, Imperial, Blob, and Machine Cult—and before we’d had the game for three weeks, I’d written a 2,500-word essay on the strengths, weaknesses, and strategies of various factions. You can build a Blue deck that’s rich in Trade and gaining back Authority, a Red deck that tries to reduce your deck size until you’re only drawing your best cards, a Blob deck that spawns huge swarms of Blobs, or a Yellow deck that does well at just about anything. (Or combinations!)

Rebecca and I have played several dozen games so far, and bought our first expansion about two weeks after the original deck; the two combined were only about $35. The strategies you can create are so much fun, and so satisfying—there’s nothing like abusing your draw-card powers to pull 10 or 15 cards in a turn and create an unstoppable war-machine of a hand. It’s also a game that allows for great comebacks; there was a time in Yellowstone where I had Rebecca down to 2 Authority, drew two straight hands without any Combat power, and then watched in horror as she marshaled an attack for 25 that blew me right down to zero. And the diversity of cards allows for at least a dozen legitimate strategies to pursue; there’s not one clearly dominant path to pursue, and even if there was, the randomness of the main deck ensures that you won’t have access to it every game.

Verdict: I can’t recommend this game highly enough, and will happily shove it in the face of everyone who enters our Cambridge domicile.

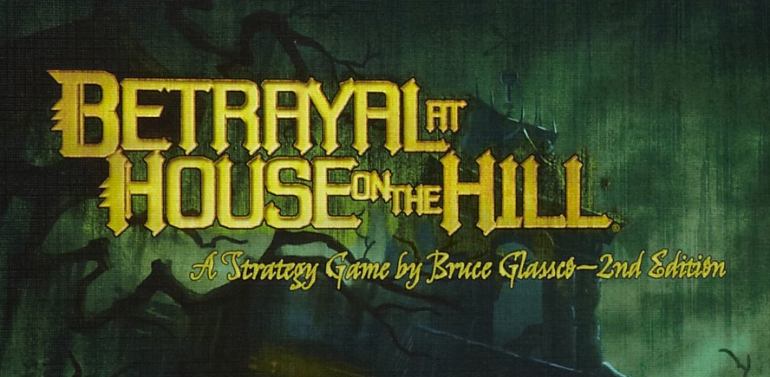

Betrayal at House on the Hill

Gameplay: Another complicated game that gets easy after a couple of repetitions. You and your fellow explorers are exploring an abandoned house, discovering new rooms with Events, Omens, Items, and effects that raise or lower your stats (Might, Speed, Knowledge, and Sanity). At some point after enough Omens have been discovered, the Haunt will begin, one of the explorers will turn traitor, and you will play out one of fifty different scenarios as the explorers and the traitor struggle for victory.

Review: I played two of the scenarios. In one, we were transported to an alien dimension and had to somehow return the house to its true dimension before the traitor, or the acid fog that was the air, killed us. In Game Two, I was the traitor, and summoned a monster called Crimson Jack to chase my erstwhile friends around the mansion; I managed to kill Rebecca, but my friend Sophia destroyed me with a mystically enhanced spear.

I didn’t like this game quite as much as Rebecca did, but it was extremely entertaining nonetheless, particularly in Game Two. The discover-it-tile-by-tile nature of the House itself ensures that you’ll never have the same geography twice, and the fifty different scenarios—all of which make different tiles vitally important—mean you’ll have to play a lot before exhausting this game. I got a really nice RPG-esque feel from it; I can’t remember if it was Rebecca or I who pointed this out, but it’s one of a couple games we’ve played that takes the infinite choices of an RPG and condenses them to a playable, DM-less, but still arresting experience.

Verdict: My heart was beating fast when I was chasing them around the mansion—I was one hundred percent into the experience. I’d absolutely like to play this again.

Mars 4:45

Gameplay: Have you played Spit? Okay, good, you’ve got the basics of this game. You’re trying to build a Mars colony by assembling piles of cards. For example, an orange Rocket deck needs an orange 1, 2, and 3 before it’s complete, and then the person who completes it gets it; everyone’s throwing cards into the middle of the table, so bogarting your fellow players’ work is part of the game. The first player to assemble a complete colony wins.

Review: There’s not exactly any subtlety to this, but it has the same manic energy of the original Spit or Egyptian Rat-Screw, or Golf, or any of those games. You have to be aware of what you’ve already put down, what you still need, and what your fellow players are working on, so you can swoop in and pirate it if need. There are complicated rules regarding scoring, but that comes later—the real fun of the game is in building up your modules, managing your deck and playing hard.

Verdict: Not the kind of thing that you play 30 times in three weeks, but a quick-playing, energizing, good game.

Ticket to Ride

Gameplay: You are a railroad looking to expand. Before you lies a map of the United States and Canada, with major cities connected by rail routes of one through six cars. Draw cards from a communal pile; when you get enough of the right color, use your little plastic train cars to connect your chosen cities. You get points for your routes, and you also get points for completing mission cards, like connecting Seattle and Houston (no matter how you do it). But beware—if you have incomplete goals at the end of the game, those points will be subtracted from your total!

Review: I’d played this a couple of times before we brought it out in San Antonio and then again in Portland. It’s a lovely game. Gameplay is primarily focused around the Goal cards; the U.S. version is big, but with 3-4 players, you’ll inevitably have Catan-like competitions to fill a crucial route before your competitor (thus blocking him/her off). You can still have fun without being super competitive, though, which is nice. It’s quite a feeling to scrimp and cadge and scratch out one route at a time until you finally connect the transcontinental route, L.A. to Boston or something crazy like that, which seemed like an impossible dream at the start.

Verdict: A known and welcome quantity, Ticket to Ride is joining Rebecca’s and my growing game cabinet sooner rather than later.

Catan: Cities & Knights

Gameplay: Catan, except with 1) invading barbarians, 2) grain-needy knights to stop them, 3) manufactured product cards that 4) allow you to upgrade various buildings and get 5) spooky-powerful dev-cards.

Review: Despite playing dozens of games of Settlers of Catan and Seafarers of Catan, mostly in college with Sid and Tadd and Dick and The Gang, I’d somehow never played Cities & Knights. I now really want to again—I only played one game, half of which was figuring out the mechanics, and would love to play again now that I’ve gotten a better handle on it. Cities are so much more important, obviously, because only with cities can you produce the commodity cards that are the game’s real currency. Knights become actual tokens on the board who can defend you from the Robber or the entire island from the barbarians when they arrive, as long as they’re well-supplied with wheat. It’s delightfully complex, so much so that you almost lose sight of the traditional-Catan objective of accumulating victory points.

Verdict: I would happily play this again. I don’t have Settlers yet, somehow, although Rebecca or I will undoubtedly remedy this for our shared library sooner rather than later.

Caribbean

Gameplay: You, greedy bastard that you are, are accumulating treasure stolen from various ports in the Caribbean. You do this by bribing pirate ships with barrels of rum to steal the treasure and bring it to your safe areas, thus earning you doubloons. But you and your fellow players are trying to bribe the same ships, so plan your strategy well and don’t get outbid! The game ends when one player accumulates a certain number of doubloons.

Review: The gameplay didn’t make sense on the box, but it promptly made sense once I started playing. The number of barrels of rum you bid is also the number of spaces you can move (pirates only work once motivated), so each player has to plan their own way of getting the most treasure back to their own safe spots in a given turn. There’s also no carryover between turns—your pirates are only loyal to you until the rum runs out—so if you plan wrong, your treasure ship can be stranded in the middle of the Caribbean, waiting for someone else to outbid you for the cargo. The head-to-head bidding element is really cool, and something I’m not used to; everyone makes their bets simultaneously before any information has been revealed, and then you call out each pirate ship to see who controls it this turn, so there’s a lovely Mexican-standoff-style feeling when everyone’s looking at each other while making their guesses.

Verdict: I don’t know that I’d buy this, but I’d certainly play it again. It’s a kind of gameplay I’m not used to, so it’s a nice palate cleanser for me between games like Catan and Star Realms.

Patchwork

Gameplay: You are a quilter! You and another quilter have 10-by-10 grids which you must fill in with quilt-pieces, which are helpfully arranged in a circle around the board. A token marks the spot on the circle where you start. The key resources are buttons, which you accumulate and use as money, and time; every time you buy a quilt-piece, you move ahead a few spots on a separate board, and when your token reaches the end of the path, you can’t do anything else. Victory goes to the player with the most buttons at the end; you lose two buttons for each empty space on your grid.

Review: This is another old favorite. Rebecca and I discovered this on the same night, in fact, as we found Ticket to Ride; this was way back at Go 4 Games in Metairie, Louisiana, when we schlepped out to those game nights. I haven’t quite figured it out yet, despite playing it several times. Some pieces are extremely expensive in buttons, but take very little time; some cheap pieces propel you several spots forward along the board. The pieces are all kinds of weird shapes, so you have to fit them into your existing pattern as best you can. And some of the pieces have buttons on them, which increases your income. I haven’t yet found the right balance between space and time, accumulating buttons and filling space on the board. That’s still to come. (Rebecca, having been born with a pair of crochet hooks in her hand, is very good at this game.)

Verdict: Bought it back in Reno for $27, so, you know, it’s good! A lovely two-player game that’s now part of the library.

The West is Gone Behind Us

We left Colorado this morning, and that means the last of the mountains are about to fade into our rearview mirror. After a month and a half of nearly continuously having them wherever we look—towering over cities, serving as loci for colossal parks, forming high passes that make our car’s engine wheeze—we are finally, officially, done with them. We won’t see another mountain worthy of the name until we reach the Appalachians.

I’ll miss the mountains. I’ve always been a flatland kid—I was born in Wisconsin, went to college in Ohio, did AmeriCorps in the South and the East Coast, and lived in Ohio again before New Orleans, which has been flirting with sea level for the better part of a century. Mountains were always a special thing for me, something so completely foreign to my experience that they were a source of wonder. Whenever we’d go to California to visit Gramma and the rest of the California clan, I would goggle out the airplane window at the Rockies and the Sierras, and stare wide-eyed at the mountain range that made up Grandpa’s backyard. I always wondered what it would be like to grow up in a place with mountains, with this sort of majestic natural creation dominating your geography.

We’ve been among the mountains for a month and a half, and they lived up to everything I wanted. Easily. We camped at Lassen Peak, in northern California, which was a whole blog post in itself; we hiked to Chaos Crags, where a rockslide centuries ago had buried an entire forest under a hundred feet of rock, and saw the five-ton boulder that Lassen’s 1915 eruption had hurled three miles from the crater. We visited Crater Lake, created when Mount Mazama blew its top off six thousand years ago, and later filled with water to create the bluest lake I’ve ever seen. We stopped at Mount St. Helens on the way up to Seattle and saw the river valley that had been scoured clean with boiling mud in the 1980 eruption. And we spent three days at Yellowstone and saw the caldera the size of Rhode Island—and that’s just the crater!!—that will one day blow the roof off the Mountain West.

Geysers are among the craziest things I’ve ever seen. We saw several blow their tops while hiking around the Old Faithful area, including Old Faithful itself (timed within a 20-minute window by some miracle of modern science), but the most special was Lion Geyser, which considerately blew when we were right in front of it. Lion was steaming hard as we walked up to it, and then Lioness (or one of the cubs, i.e. small nearby geysers) started steaming and belching water two or three feet in the air, and Rebecca and I looked at each other and said “This might be about to happen”, and then there was the deep rumble and roaring in the earth that gave Lion its name, and then it blew!! It blew twenty feet in the air, right in front of us, water so hot that it vaporized almost immediately upon meeting the air, enveloping us in a cloud of warm, soft, sulfur-scented steam. It was spectacular, incredible, all the adjectives you could throw out there.

It was the geysers that helped me realize the sheer scale of Yellowstone. When I heard that Yellowstone Lake, a 140-square-mile body of water, filled only about 20% of the caldera*, that was mind-blowing enough. But seeing the field of geysers—and it is a field, acres of scanty grass and bleach-white stones and vibrant red-orange bacterial runoff and bubbling geysers and transcendent, color-filled pools—and seeing the plumes of steam from dozens of geysers, which had been erupting and erupting for Lord only knows how many years, and realizing that not only were they all powered by a single source, but that that source was exerting only the tiniest part of its true power to make all these fountains fire on cue… that was when I got some idea of the power of Yellowstone Caldera.

That was the last and the biggest of the mountains. We’re heading east on Route 34 as I type this, and by the time I post this, we’ll have long since joined up with U.S. Route 76/80 and followed it all the way across Nebraska to Omaha, where we’re staying tonight. Another day and we’ll be in Chicago, and after that, we can hardly even be said to be traveling; I’ll be home in Wisconsin, then to an adopted home in Cleveland, and then to Rebecca’s home in Philadelphia… and then our new home, our together-home, in Cambridge, MA.

Only two weeks left, maybe two and a half. I can’t believe how long it’s been going, and I can’t believe how fast it’s gone.

*It’s not fully in the caldera, though; if it was fully within the caldera’s borders it would be a higher percentage.

The Short, Abortive Story of Our Yosemite Visit

So, for the first time in our trip, we are more or less entirely cutting a destination out of the schedule. To my great disappointment and mild relief, that destination is Yosemite National Park.

Slight background. Our original plan was to schlep west across the Southwest until we reached L.A., then to turn north through the Sierra Nevada parks: Sequoia National Park, Kings’ Canyon, Muir Woods, and finally Yosemite, before continuing triumphantly to Modesto, CA to see my grandmother.

A bunch of things interfered to gronk this plan. First, Rebecca was ill for most of our stay in L.A., and was still feeling a little shaky; I’d also had a very brief bout of it, and so we weren’t super eager to spend a lot of time in the woods. Second, our stove broke; the regulator, a metal tube that connects the propane bottle to the stove and admits the desired amount of gas, decided that any gas was bad gas and we shouldn’t have it. Facing the prospect of six more days in the woods with no hot food, and with no reservations to honor or break, we more or less looked at each other and said “Fuck that”.

We went instead to San Francisco (which is on another planet than the rest of California; it never dipped below 104 degrees during our trip across the San Joaquin Valley, but when we got to Cousin Jerry & Judy’s house, people were wearing jackets and pants in the streets!), to Oakland for a day (see Rebecca’s post on the Athletic Playground), and then on to Modesto for several days. The revised plan was then to camp in Yosemite for a few days before hopscotching on to Reno.

The great advantage of our trip thus far has been that we don’t have a fixed schedule. We’re staying almost exclusively with friends and family members in the cities we go to, and when camping, we’ve so far gotten away with just showing up and finding campsites. With some planning, it worked at the Grand Canyon; it worked at Joshua Tree, and it worked in Sequoia National Forest. This allows us to change our schedule on a whim—if we want to spend an extra day at the Grand Canyon, or to go to Sedona, AZ, or skip Albuquerque, or randomly go to San Francisco. It’s freeing and fun.

The big ‘ol disadvantage is that it’s a pain in the neck to find campsites on minimal notice, especially if you’re trying to secure a spot in one of America’s three most popular national parks, on one of the three biggest holiday weekends of the year.

We tried to find a spot in the camp’s only currently open walk-in campground, getting up at 5:45 this morning and schlepping up the mountains to Yosemite. Nothing doing. No open spots; even the three families who were leaving already had people to take their spots. We drove entirely through the park, stopping for a 20-minute nap because we were both exhausted, and out the Tioga Pass to the town of Lee Vining. We’d heard that we could find spots outside the park near Lee Vining, but the local ranger station said, no way; they’re full. There are some at Lundy Canyon a few miles up the road, though. So we went a few miles up the road and into the canyon. Nope; no free spots. (You’re not allowed to camp at random places in Yosemite, because bears.)

By this point we had both pretty much given up hope that there would be anything available within 100 miles of Yosemite. We discussed options; get a motel and try again tomorrow, go to a nearby town and try again tomorrow, go to Reno and try again later, or simply give up.

Obviously we picked “simply give up”. Which I’m okay with, but for a weird reason. I’ve never had any particular attraction to Yosemite. I went to the Grand Canyon when I was little with Oma and Opa; I wanted to go there again. I’ve been reading about Lassen Peak and Yellowstone and Crater Lake in volcano books since I was a little kid. But Yosemite—nope.

That was before we started talking about going there. But Rebecca’s father had lent us a National Geographic that was completely about Yosemite, and that spoke about it in the most spiritual terms. The articles were written by people who loved the park and whose families had been around it for literally generations. And, you know, I began to get the idea that we couldn’t half-ass this park. I could show up at the Grand Canyon and see it, spend a few days there, hike it somewhat, and not feel like I had missed out on any fundamental experiences. But I felt very strongly that if we couldn’t take our time, get a good campsite and really experience Yosemite, that it was a different animal than most of the other parts; that we were better off leaving and coming back later to really grok it than trying to get only part of the experience.

So we are now in the car (or will have been in the car, when this posts), on our way to Reno, where we will at the first available moment spend our time booking reservations at all the remaining parks we will go to. There’s obviously the ability to go to the bloody things, but there’s also the allure of less stress. We schemed and plotted and got a night at a random campsite in Flagstaff and woke up bloody early to get to the Grand Canyon and get to the Desert View campsite in time to snatch one of the walk-in spots. That stresses me out. So we’re going to sacrifice a little flexibility in order to have guaranteed spots, or at least as guaranteed as we can get, from now on.

Rebecca Post: A Playground For the Rest of Us / Mo-ratorium (or, In Me-Mo-ry) (or, Mo-mento Mo-ri) (in Mo-desto, CA)

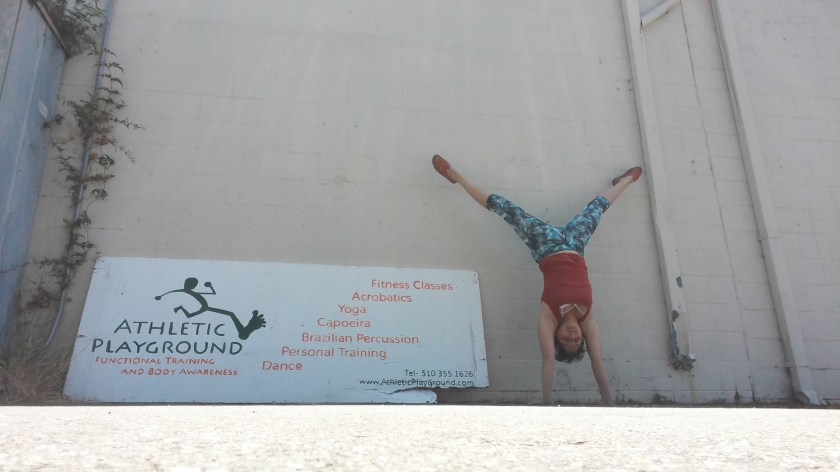

A Playground for the Rest of Us

This is the part of the San Francisco Bay Area that I’m most familiar with:

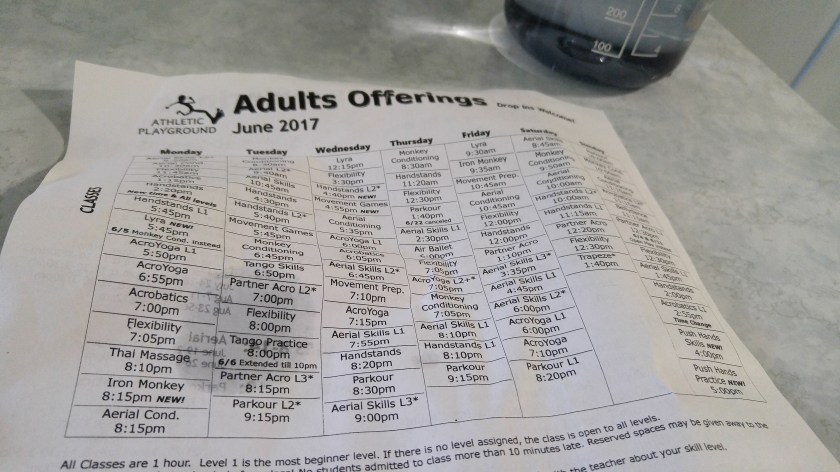

The Athletic Playground is a movement studio focused on the “monkey arts”: Handstands, aerial silks, trapeze, parkour, acroyoga, flexibility, tango… you name it. These classes are primarily for adults, with some “mini monkey” classes targeted towards children.

I was doing research on movement or play-based non-profits, my eventual business goal, when I learned about the Athletic Playground through the internet. Deciding immediately that I had to see what it was really like there, I petitioned the Social Innovation/Social Entrepreneurship department at Tulane University to award me the Changemaker Catalyst Award in order to do so. According to my initial plea, it sounded something like this:

I must investigate this program firsthand; this is the single best training I could give myself at this time. I have already made contact with one of the founders of this program, and she has invited me to come see what they do. There are four categories of research that a site visit to the Athletic Playground will allow me to investigate:

1) Business model: Are they self-sufficient? How do tuitions and salaries get realized?

2) Classes: How do the classes work in practice? How many students per class, and what kind of training/credentialing do the instructors have?

3) Environment: What makes the Athletic Playground function? How are the community events received locally? What works for them, and what could eventually be incorporated into the Acrodemics model? How do they manage to serve a population where more than 80% of high school students live below the poverty level?

4) Unknown: What do I not know? (This may be the most important category of my research.) What is only discernable through a site visit? What is unknown to me to even ask, which I will discover along the way?

-March, 2016

So, to recap, last year I successfully convinced some kind people at Tulane that they should give me money to fly cross-country to the Bay Area and take classes at the Athletic Playground for a week. (I still can’t believe that worked.) I flew up mid-June of 2016 and did just that- stayed at a friend’s parent’s home and took as many classes as I could fit in that week.

Now, almost exactly one year later, I got to stop by this community again for a day and a half- enough time to take two classes and one session of open play.

This place is so special. There’s nothing like it anywhere I’ve been. It’s a studio, playspace, gym, movement workshop, and purpose-designed playground that has fostered a community of movers and shakers, literally. One of the classes is called “monkey conditioning.” I have been welcomed with smiles, hugs, laughter, and an easy warmth that permeates the whole double warehouse. Part of this kindness is intentional. Unlike a typical gym space, macho one-upmanship is not tolerated. Neither is shirtlessness. Both rules designed to make everyone feel comfortable in a space specifically catering to play.

Athletic Playground is located in Emeryville, CA, about halfway between Oakland and Berkeley. Emeryville’s median household income is $69,274 and the median age is 33.5, according to the its official website. Over 50% of its residents have a college education. So, yeah. Although 14.3% of its residence earn income below the poverty level, you wouldn’t necessarily know it. (This is significantly less than California’s average of 20.2% of residents below the poverty line.)[1] Directly across the street from AP is a public K-12 school that looks like this:

…with a statue of the Buddha in the courtyard.

Also, there’s a bilingual school.

Also, there’s another bilingual school.

Yes, those are three different schools, all moneyed, all within a three-block radius of AP.

AP isn’t cheap. A drop-in class will run you $25. The packages make that number a bit better, but it’s not designed to be accessible for people without disposable income. This was kind of a shock to me- my vision is to make movement classes, specifically acroyoga, accessible to underserved populations. AP, in contrast, is a for-profit enterprise with a niche audience. When I spoke to the CFO last year, he told me they are working on a limited scholarship program. But their goal, perhaps because of the significantly affluent location, is not primarily focused on bringing their services to the poor.

Maybe they don’t need to. There’s enough money floating around Emeryville, Oakland, and Berkeley that their services are accessible to most of the population.

Andy reminds me that businesses need to have priorities. AP’s priorities include paying its teachers fair wages, and offering roughly a billion classes each week.

Acrodemics, the name of my program, is to be specifically designed to be accessible to underserved populations, specifically school kids ages 6-18. When I set up in a brick-and-mortar, my financials will look very different from the Athletic Playground. Presumably, so will my operations.

“If it’s inaccessible to the poor, it is neither radical nor revolutionary”

-Unattributed

Neither radical nor revolutionary is my goal with Acrodemics. Ok, well, maybe revolutionary. Therefore, I hereby proclaim my intent to make movement classes accessible to underserved populations- whatever that means.

Mo-ratorium (or, In Me-Mo-ry) (or, Mo-mento Mo-ri)

Our four cactuses, all named Mo, have died.

It is a sad day.

Our poor succulent friends have left us and ascended to another plane, probably with more shade and less heat.

Today is the day where we apologize to each and every Mo for not realizing that succulents aren’t the same thing as cactuses- and the day where we recognize our presumptions that cactuses could survive the unrelenting +120° heat of the car. Well, maybe we should do some research on cactuses. Or just buy a couple more and hope they don’t go the way of the Mo. Yeah, that’s probably what we’ll do.

Big Mo, Maurice, Little Mo, and Mo-mo, you will be missed. Especially by Mr. Why, who doesn’t quite understand why he had to stand in a graveyard for 3 weeks.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Source: http://www.city-data.com/poverty/poverty-Emeryville-California.html

Mountain-Climbing, California Caving, and a Natural Waterslide: One Day on Our Road Trip

Above: We don’t have wine up in these here hills, but we do have Jim Beam and Los Angeles challah, so Rebecca and I had the world’s worst (i.e. most Reform) Shabbos possible.

The following post was written on 6/24/17, when we were still in Sequoia National Forest; I’m posting it now because I just got Internet again. this first part was written at like 7 AM.

The first thing you notice about our campsite is that it’s never really quiet. The Grand Canyon, when it fell silent, was silent; there were birds and insects and things, but the lack of human-caused noise and our position on the canyon’s rim meant that when people went to bed, so did the background chatter. Here, the Kern River is constantly roaring quietly in the background, audible whenever the conversation ends and the people fall silent.

The road we’re on wouldn’t exist if not for the River. Over God-knows-how-many years, it cut a trail down from the tops of these mountains, the foothills of the Sierra Nevada. We followed it all the way up from the San Joaquin Valley, hugging the wall of the canyon it carved. I always find it so striking how geography determines civilization here. The few towns and campsites that we found coming up into the mountains—Wofford Heights, Kernville, and the like—are all right on the river, in whatever flat places allotted them by the mountain range.

We’re at Hospital Flats, about halfway up the canyon, deep into the Sequoia National Forest. It turns out, moreover, that there’s a more-than-semantic difference between Sequoia National Park and Sequoia National Forest. The Park apparently has the sequoia trees that we came here to see, and the Forest, despite the name, does not. At least not at Hospital Flats—there’s plenty of trees here, including several that considerately shade our campsite, but nothing over twenty or thirty feet high. Except, of course, the gigantic mountains that surround us on three sides. They’re all big and brown, or big and green, or studded with reddish scarps; some have trees silhouetted at the top, tiny shapes against the sky, that you know for damn sure are seventy feet tall.

For a flatlander like me—raised in Milwaukee, lived in Ohio and Louisiana and New York and D.C.—it is awe-inspiring to see mountains wherever you go; in the hazy distance when you’re driving on the plains, in the background of the city you’re in, or range after range on the road north from Los Angeles. There was a Calvin and Hobbes strip in which Calvin, as Spaceman Spiff, is exploring an alien planet whose mountains and valleys turn out to be nothing more than the wrinkles in the blankets of a giant alien bed. After driving through the northern L.A. mountains, I now understand that; those mountains look like nothing more than the wrinkles and folds of the world’s largest bedsheets.

So. We have been in Los Angeles for the past six days or so, and I haven’t written about it because we haven’t done much worth writing about; Rebecca was sick for most of the trip, so she hardly made it out of her cousin’s house (shout-out to our latest kind hosts, Natasha and Michael), and I only made a couple of short trips. One was to the Natural History Museum, which is always a should-see when I visit a new city. Another was to my cousin Leota’s play, which was billed as a mixture of The Rocky Horror Picture Show and Hedwig and the Angry Inch, and turned out to be exactly that; and to see my Grandpa, Aunt Val, and Uncle Larry, an hour and a half east of where we were staying. (I have to admit, I’m wavering on my never-getting-a-smartphone stance. I have now gotten lost twice in two trips in L.A. when I had to navigate by handwritten directions alone.)

Now we’re up in the rather-misnamed Forest, and will probably spend two days here. There are a bunch of companies that offer to take you whitewater rafting, which I would love to do, and presumably there must be trails into these mountains someplace. My goal is to climb at least one of these mountains while I’m here. Unfortunately, there are no maps of nearby trails in our campsite, so I’ll try to get one when I get into town.

Rebecca has just lurched out of the tent and in the direction of the car, so I am going to finish writing for now. Further bulletins as events warrant.

and then the events of the day happened

chronicled below

Update from a darkened tent: serendipity wins!

One of the nice things about this trip is the unpredictability. When we come to a new city or a new national park, outside of seeing people we know, pretty much everything is unplanned—we just go places, see things, hike trails, etc. We don’t do a lot of research beforehand, we just let things happen as they may. Today, when the park ranger came around to check everyone’s tent in the morning, I asked him for maps and he handed me a pamphlet, and let me take a photo of a pencil sketch to a waterslide (????) somewhere way up in the canyon. I told him we were looking for someplace to hike today, and he recommended Saddleback Baclesack Sackbaddle Packsaddle Cave. So right away our day was decided: do the trail, all the way to the cave, then find that waterslide!

Man, I may not finish this today—I have so much to write about and it’s already almost 11 PM, which is really late by camping standards. Rebecca and I were talking about this today—being in bed by 10 PM is about standard. Getting up is another story. Early birds rise with the sun, which is usually around 5:30 or 6. 7:00 is usually when I stop ignoring the sun and crawl out of the tent in search of breakfast. 8 AM is like, all right, c’mon, let’s go sleepyhead. 10 AM is inconceivable sloth.

That’s campsite life. We have a pretty big plot of land where we pitched the tent; it has a rudimentary fire-pit, a picnic table, a lot of huge rocks (there are huge rocks everywhere) and a couple of trees that Rebecca strung a hammock between. We’re right next to the pit toilets (oh, joy) and the water pump (GENUINE JOY), and there’s an access road right nearby. The river is maybe thirty feet away, and the whitewater is so loud that you can’t hear the other person inside our own tent if your head is turned away from them.

So we walked outside the gates of Paris left this morning with our hiking bags packed, this including four water bottles, beef jerky, almonds, Ritz crackers, peanut butter, trail mix, carrots, and lots of little trail things—chapstick, sunscreen, handkerchiefs, a knife, my camera, and other odds and ends—and headed north, up the canyon. After quite a bit of driving around and a stop at a bed-and-breakfast helmed by a saint named Eddie who gave us directions and Rebecca coffee, thus breathing life into her like Trinity reinvigorating Neo, we found Packsaddle Trail opposite Fairview Campground. We got out of our cars, found our sun-hats, sunscreened up, crossed the road and began to hike.

The trail goes up a mountain. It’s called Mountain 99 on the mile-markers. I don’t have the map handy to tell me its proper name, but while we were on it it was called oh my God we’re climbing this fucking mountain. The trail guide said it was 2.3 miles and that we would gain 900 feet in elevation. Bull-shit. It took us two and a half hours to make it to the cave, and that’s probably because we started by climbing Mountain 99, which I think was over 900 feet by itself! It was hot; we started around 10, and we took shade breaks whenever possible, but it was still upwards of 94 degrees while we were there. The path was beautiful, lined with all sorts of weird plants—bushes with red flowers that held all their leaves strictly vertical, dead vines with heart-sized spiny fruit that had burst open and dried up, cloudy white flowers in great green bushes that attracted bumblebees by the half-dozen, ghostly white dead trees with long slender limbs that stood starkly above the green vegetation, little sonofabitch sticker-prickers that wormed their way into your socks and gnawed at your ankles, and a dozen other varieties.

We walked at first up rocks that had been laid down atop the trail, then on dirt among the rocks, and then just dirt, red-orange dirt shading gradually to brown. We passed naked red rock jutting out of the mountainside, and rested in the shade of green skyscraping bushes. Flies buzzed around our ears. Bumblebees doodled around our knees (the biggest of them, the size of thumb-joints, were nicknamed Rumblebee and Thunderbee). The trail bends in such a way that you can’t really see more than the next turn in front of you, so we were stuck dogging it all the way up Mountain 99. We were on there for an hour, and it was a long hour, and we were resting near the summit when some hikers coming back told us that we were at best halfway there. We were too tired to even grumble.

At last we topped the mountain and began walking down the other side. The trail just kept going. Beyond the mountains we could see from the road was an entire second range, with its own gorges and pricker-bushes and a path winding down the back of Mountain 99. Blessed Downhill, our savior be! We walked down the side of the mountain, and at length it became clear that our path led into the valley snaking between two mountains straight ahead, the left one with striking slopes that were almost entirely covered with low, brown, dead plants, except for the odd tree and one slope that was green and vegetated, perhaps in some kind of rain or wind shadow in the lea. A ribbon of bright green trees ran in the valley between the mountains, and I may be a rube from NOLA whose idea of getting in touch with nature is noodling around in City Park, but I know running water when I see what grows next to it.

We stopped to rest in the cool shade beneath those trees, listening to the stream chuckling merrily past us and watching water-striders step delicately from bank to bank. We wet washcloths and bound them around our heads or crammed them beneath our hats. I had the idea of getting walking-sticks, and soon each of us had a long (dead) staff, more or less straight and properly debranched. On we went. We crossed the stream a second time, and then a third, getting higher and higher into the cleft between the two mountains; we each acquired second walking sticks, which I have to tell you, are the hiking-friendliest invention since someone figured out how to enclose water in a container. They make uphills bearable and downhills downright simple. Following the footprints through underbrush, over a fallen tree the size of a transatlantic cable, through mud and over stone, we arrived at last at a turnoff to go up the brown-sided mountain on the left. We were low on water, in “Let’s walk ten more minutes and see” territory, and I had given up almost on finding the damn cave—I had seen a couple of giant boulders that looked cave-mouth-ish and been disappointed—and then as we were trekking up the side of this yet another mountain, I followed the path with my eyes forward to another rocky scarp and yelled “There it is!!” A black hole in the side of the cliff. We barely felt the last few hundred feet as scrambled to the mouth of the cave and looked inside.

That cave was worth every step, every bug in your face, every time we had to fight through undergrowth that overgrowthed the trail. It was vast. It must have extended at least a hundred feet into the mountain (Rebecca guessed 150), so far back that you could get to where no light from the doorway was visible—no light at all—and still have another two or three chambers beyond there to explore. Ten steps in from the mouth, the temperature dropped at least thirty degrees. Little crystals glistened in the light from our lamps. Weird pillars and mushroomy rocks, stalactites, grottoes, hidden chambers, holes in the rock that led to other spaces. The last chamber was too narrow to enter on our feet, so of course we crouched down and duck-walked as far in as we could, shining the lights on every available surface and occasionally uttering “Oh, wow” or “Look at this!”. There was graffiti on the walls, not too destructively, just names and places—and dates, going back more than a century, some carved in pencil with old-fashioned handwriting. I told Rebecca this was one of the many ways in which the wilderness makes me feel small. Here we are, two ants scrabbling around in this cavernous space with all this rock above our head, and the cave is almost all the way up the mountain; only the tiniest bit of the peak, seventy or eighty feet, lay above us, and yet it dwarfed us with its inconceivable weight.

It’s getting late here so I’m going to wrap this up shortly. We explored the cave to our hearts’ content. We rested there for maybe an hour, ate, drank, then packed up at length and headed downslope. The journey back didn’t take that much less time than its cousin—maybe two hours and a quarter on the first, an hour and a half for the second—but it felt like we were motoring. The walking sticks were absolutely invaluable assistants. We went back down Brown Mountain, past the creek, past the creek, past the creek, up the side of Mountain 99 (while we were just past the crest, Rebecca informed me that we’d been going for an hour, which, what?!) and down the other side. I’ve never been so glad to see our car, or a water pump. We stumbled to the nearby campsite, plopped our butts in the shade of the outhouse, and drank as much water as we could physically hold.

Although Rebecca was dead tired, I talked her into/drove the car up even farther into the mountains, following a memory of a paper map, to the waterslide. We drove around a beautiful mountain road with rocks on our right, majestic, reddened, steep-sided cliffs, and plunging valleys between tall, gruff mountains marching to our left. We made it to the correct place on the first try, parked, walked the last 0.8 miles uphill (and let me tell you that is a very long distance when you hiked up and down several mountains), and found… an extremely flat rocky patch with a swift-flowing stream and tiny waterfall; the stream rushes downslope with such force that it can propel passengers into the pool below the falls.

Of course I had to do it. The stream must have been fifty degrees, if not forty, and after some time acclimating myself to it, I sat down in the stream in my bathing suit. At first, I didn’t move, and so I pushed forward with my hands and started to go… and then a little more… and all of a sudden I was going down into the little bowl that formed right before the falls, and was propelled out of it in a froth of white water and SPLASH into the pool, which was like being flung into the frozen lake from the Caves of Fire and Ice. Good God was it cold. Rebecca said something on the lines of “No fucking way am I doing that.” So of course I did it four more times, the last in the “express lane” where the water runs even faster than in the main stream, and which flung me bodily downfall in a much more expeditious way. It was an incredible rush, and upon seeing a family of three show up and start doing it, Rebecca finally went along and did it also—and was promptly flung down the river and into the pool, squawking involuntarily all the way.

We dried off, swatted flies, hiked back to the car, drove down through the vistas to our campsite, attempted to cook dinner, learned that the camp stove was not working, defiantly ate bagged salad instead, played dominos (Rebecca’s teaching me), did dishes, went to the tent, discovered it had hundreds of ants on it for no known reason, shrugged, did what we could to disrupt their scent trails and make their lives miserable, and went to bed, after I read Rebecca the remainder of the first half of “The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar”, which she had fallen asleep to the night before.

And that was that. Pardon me while I BED.

The Mandela Effect is Pseudoscientific Bull

The most basic problem with the Mandela Effect is that although it tries to be scientific, borrowing language from the world of physics, it doesn’t hold up when confronted with the most fundamental test we can apply to science: Is it testable?

If you’re not familiar with the Mandela Effect, its thesis is that people remember things that didn’t actually happen. They remember incorrect movie quotes, mistaken product names, and misdated events, such as when Nelson Mandela died. They also take the subsequent step of chalking those mistakes up to, instead of human fallibility, alternate universes bleeding over into our own. Since numerous people make these mistakes–that since many people remember Darth Vader saying “Luke, I am your father” instead of “No, Luke. I am your father” in The Empire Strikes Back, the best explanation is that our universe somehow merged with an alternate universe in which the quote actually is “Luke, I am your father”, and that everyone who remembers the wrong version is instead remembering an alternate-universe version of the movie.

I could write “That’s stupid” and leave it at that, but I want to actually address what’s wrong with this theory instead. The most basic problem with the Mandela Effect is that although it tries to be scientific, borrowing language from the world of physics, it doesn’t hold up when confronted with the most fundamental test we can apply to science: Is it testable?

In the strictest sense, we can’t prove beyond doubt that any scientific theory is true, because tomorrow an experiment could prove it false. In other words, scientific theories are falsifiable. They make predictions or claims that can be tested and either confirmed or refuted by the evidence. Plate tectonics explains how the continents move and have moved, and it has a lot of evidence in its favor. Based on this, we can project where the continents used to be. But if we find evidence contradicting where we think the continents used to be, then we have to change our theory to account for that. We have to take this new evidence and say, how can we modify this theory to account for what we are now observing? Or do we have to throw out this theory and create a new one that accounts for what we’ve now observed?

That is the essence of science: making claims that can be confirmed or refuted by experiment. Rigorously testing things is what scientists do. It’s why they exist.

The Mandela Effect sounds like science, it uses words like “parallel universes” and “quantum computers” that come out of the scientific vocabulary, but it isn’t science. Why? It doesn’t make testable predictions.

If I had to boil down the Mandela Effect to a one-sentence theory, it would be this: “Parallel universes are interacting with our universe in a way that causes some people to have memories of things that did not exist in our universe, but do exist in a parallel universe”.

Great. How can I test that? How can I set up a test that says “If this test succeeds, the Mandela Effect is probably real, and if it fails, it’s probably false”?

I can’t. It’s impossible. The Mandela Effect is based on the memories of individuals, not any kind of testable, real-world evidence—in fact, the whole point of the Effect is that real-world evidence doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter what Darth Vader actually says in The Empire Strikes Back, it matters what people believe that he said. It’s all happening inside people’s heads! I can’t make a testable prediction about what you remember or why, because I can’t get inside your head. I can survey people; I can do a poll and ask non-leading questions about specific events and what people remember, but all I’m doing then is finding out whether people remember things correctly. No matter how many people I ask, I won’t have anything to confirm or refute the related but separate idea that parallel universes are responsible for people’s false memories. I can’t test for the existence of parallel universes; if you can, tell me, because we’re about to revolutionize physics. So I can’t prove it.

If I can’t prove it, it just exists in the same wibbly-wobbly timey-wimey land as the existence of the Loch Ness Monster. Why would parallel universes be responsible for the Effect instead of, say, little green men from Mars? Or the government? Rogue fairies? Amhotep? The immortal spirit of the Sun itself? Seriously, why would it be due to a parallel universe and not because of any of those things?

None of those explanations are testable and disprovable, at least not if I’m determined enough. They’re all completely dumb. That’s what the Mandela Effect is doing. It can’t be proven or disproven in any way that science can grapple with. You might say that just means that science is broken or useless in this instance, but science, again, is the process of asking ‘How does this work and what evidence is there to show it’? If there’s no evidence to support the Mandela Effect, it’s down there with fairies on the level of believability.

For more on what actually is happening with the Mandela Effect, Snopes said it better and more comprehensively than I can. I only have this to add:

The root of the Mandela Effect is fallible human memory running up against perfect, irrefutable memory, losing, and refusing to lose.

We’re not used to dealing with complete and perfect information. One of the things I noticed, while watching 40 minutes of a Mandela Effect “No, no, it’s really happening!” video, was that a lot of examples they cited as universe-colliding movie quotes–where people remember the movie quote incorrectly–were from the pre-Internet era. Star Wars was 1977. Snow White, 1937. Jaws, 1975. Field of Dreams was 1989; Silence of the Lambs, 1991; Forrest Gump, 1994; Interview with the Vampire, 1994.

All of those movies came out in an age where people would see them in a physical theater and go home. If they liked them, they’d go see them a second time. There was no Internet where bootlegs or stolen copies could be quickly and easily distributed, and there was no YouTube where people could post and watch clips of the most famous scenes. In other words, the only source most people would have for the line would be their memories.

And memory is faulty!

If the Mandela Effect is real, then it must be happening all the time, not just in the pre-Internet age. Logically, it should be happening right now as well. But there aren’t any post-2000-or-so movies where a lot of people remember a misquotation; certainly, there are none from the 2010s. Because everyone can watch the relevant clip on YouTube over and over if they want to. There’s not that space that there was in the 1980s where people have room and time to get it wrong.

We’re not used to that. People aren’t used to having Snopes, or the collective memory of the human race, hovering over their shoulders. And nobody likes to get things wrong, even little things, especially things that they’re sure about. We would rather believe anything else, even a crazy, unprovable thing like “Memories from alternate universes are appearing in my head”, than believe that the things we are certain happened actually didn’t. Because it calls everything else we remember into question, which is uncomfortable and scary (as it should be!). And because, dammit, we just don’t want to.

Update: Not Dead, Just In Arizona (The Grand Canyon Says Hello)

At the Grand Canyon, they lack Wi-Fi, except in certain areas–the visitor’s center, the general store near the Desert View campgrounds, presumably a few other places–and I lacked anything like the motivation to get out my clunky, clumsy, hopelessly out-of-place electronic device and haul it over to one of them just to type up a blog post. If you’ve ever been to the Grand Canyon before, slash camped out at it before, it’s…

I mean, it’s fucking incredible. It is literally not credible. I had to train my mind out of thinking I was looking at some kind of backdrop for a colossal movie set, because things that large and beautiful and spectacular just don’t exist in the normal world where I normally live.

We hiked into it, twice–we did the Bright Angel Trail up to the 1.5 mile mark, two days ago, and yesterday we did 1.5 miles of the South Kaibab trailhead. The Bright Angel trail is located on a fault line, which makes it about the coolest thing I can imagine; I don’t know about South Kaibab, but it is extremely steep.

Walking into the Canyon, and walking back out, is an exercise in humility. Forget cell phones, Wi-Fi, electricity, and all the rest. That was never even an option. There’s no ski lift, there’s no elevator, there is no way to go down or up except by hiking. And it is hard. There are signs plastered all over the tourist areas of the canyon that make it very clear–Rebecca put it best; park rangers are really good at clear and direct communication–that the Canyon is not your friend, it is not a casual day-hike, it is a serious and physically demanding journey that will fuck you up if you don’t bring enough water or food, or get overambitious in any way.

“Going down is optional. Coming up is mandatory,” said the sign at Cedar Ridge, at the 1.5-mile mark on the South Kaibab trail. There was no water down there, unlike at Bright Angel the day before, so Rebecca and I carried five full water bottles between us, totaling probably six and a half liters. We brought two packets of trail mix, beef jerky, Triscuits Wheat Thins and peanut butter, generic saltine crackers, Cheez-Its, two apples, carrots, and probably some other stuff I’m forgetting. (You have to bring salty snacks to replace what you’re going to sweat out.) We brought two tubes of sunscreen, big shady hats, sunglasses, and chapstick.

Before we were out, we had drunk every last drop of the water, eaten most of the food, sunscreened up maybe three times each, and been devoutly thankful for the hats and glasses and light clothing we were wearing. The Canyon is as temperatureamental as anywhere I’ve ever been; you can be sitting in the sun and it’s 90 degrees, and then the wind comes up and it feels like 50, not half a minute later.

We made it to Ooh Ah Point, 0.9 miles from the canyon rim, and decided to hike the remaining 0.6 miles to Cedar Ridge, a drop of 440 feet. That was our goal.

We made it, and the view was spectacular, and if it weren’t so late at night I would make some effort to upload photos and put some of them here for you–which I really will do, some day. (WordPress lets you schedule posts so they come out later, which is nice when it’s 1:30 AM and you want to write something.)

But I want to convey to you just how hard it is to hike even the little bit of the Grand Canyon that we did. (One day, we will return, and we will hike rim-to-rim–South to North, crossing the Colorado River on the way.) Not because look how badass we are, but because it was humbling. Going down is whatever. Going up consumes the entirety of your attention.

The path up from Cedar Ridge is in the Redwall sandstone, reddish-orange, slaty rock. The sand of the path is orange. There is not much shade. The grade, well, is steep–440 feet in not quite two-thirds of a mile. The path is sometimes even, sometimes rocky, sometimes dug out; a crew of National Park Service AmeriCorps volunteers were resurfacing it, which meant digging out the dirt areas between the logs that define each step, filling in the areas with rock from the canyon wall, and spreading a layer of dirt over the top of that. We walked over some areas with just the rock, which was fine, and a lot of areas that had been dug out but not yet filled in. Two-foot gaps in the orange dirt between the logs. You step from log to log, or you trudge through each hollow, or you balance on the larger rocks that line the side of the path, but climb it you do. It’s not glamorous. You’re just putting one foot in front of the next, in front of the next, in front of the next, up the equivalent of 112 flights of stairs. And you’re doing it at 8,000 feet above sea level.

We drank every drop of our water. We took breaks under trees, under overhanging rock faces that were cool to the touch and provided us some shade. The rangers tell you not to hike between 10 AM and 4 PM in the summer; we had started around 10, rested at Cedar Ridge until maybe 12, and hiked up from 12 to 1 when the sun was directly overhead–even so, there was some shade, and we used it.

We sang songs, probably irritating the other hikers, but we didn’t care. The day before, we’d run through a number of old marching/folk/work songs–“What Shall We Do With the Drunken Sailor”, “Willie The Weeper”, “Erie Canal”, “British Grenadiers”, “Drill Ye Tarriers Drill”–before finding that “When Johnny Comes Marching Home” has the perfect beat to hike to; when all the verses had been sung, we made up our own, naturally about hiking. “And they’ll all go tumb-ling down from the can-yon wall.” We made up a story in which Andy and Rebecca kept slipping off the trail and tumbling all the way to the bottom, eventually deciding to simply stay at the bottom and build a cabin there. Twenty years later, they hike up to the top just to see what it’s like now; the hikers tell them that Trump is no longer president, but Steve Bannon is still in power–“And his storm-troop-ers, they wait on the can-yon rim“–and of course they decide instead to stay on the canyon floor.

When we made it back to the canyon rim, it was the last thing of consequence we did that day, other than urging some idiot tourists away from an elk that was drinking at the water fountain (pictures to come, SOMEDAY), going back to our tent, napping, reading, cooking dinner on the camp stove, eating, building a fire, cleaning up after ourselves, stringing up the hammock, playing cards, watching the stars and the Milky Way come out, and reading (me)/listening to Roald Dahl’s “The Mildenhall Treasure” from The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar (And Six More) before going to bed.

Time works differently when you’re camping, I guess, even when it’s camping at a designated campsite with running water and actual bathrooms. In the cities we’ve gone to so far–Houston, San Antonio, Austin, Santa Fe–I’ve been like, “What are all the things I want to do in this city? How can we do them in this amount of time?” It’s been very schedule-driven/planning-driven–what are we doing, where are we going, with whom are we staying, etc. At the Canyon, it was the opposite of that. Once we secured our campsite, it was like, we have no schedule and are accountable to no one. We can do whatever we want, whenever we want, or nothing at all. We woke up with the sun, at 7 or 8 AM, and went to bed around maybe 10:30; we rarely looked at a clock. Rebecca told time by measuring the distance from the Sun to the horizon with her fingers.

What I’m trying to say is that one does not keep up with news, or write blog posts, or really do anything to connect oneself to the world outside, when one is a) camping and b) spending one’s time next to an incomparable natural masterpiece.

Hence the delay.

I’m nearly 1,400 words in and I’ve left out most of everything we did over the last week. No mention of Yavapai Geology Museum or the geology tour we received; not a word about the Watchtower, or everything we did wrong in our first camping trip, (Rebecca has floated the idea of a post in that department), or the Rim Trail, or anything about Santa Fe at all; the balloon ride Rebecca surprised me with, the living RPG that was Meow Wolf, the New Mexico History Museum or the Governors’ Palace or the wonder that was driving into New Mexico through a towering hundred-mile thunderstorm; not a word about the Caves of Ice and Fire (no shit, that’s a real thing) or the slightly overblown majesty of Meteor Crater, or even our first night camping in a rent-a-site campground in Flagstaff. Hell, we’re in Sedona, AZ now, and I haven’t said shit about that. And I won’t. Why? Because I’m doing the modern-world thing again where I abuse electric light, and it’s 1:23 AM by my clock and it is past time to be in bed so I can get the hotel’s complimentary breakfast that ends at 9:30, the skinflints, and be on the road in time to get a campsite at the other end of the six-hour drive to Joshua Tree. Those stories will have to wait. Tomorrow there’ll be more.

Maybe It’s Okay to be a Tourist… Sometimes… a Little

In the (almost) three years I lived in New Orleans, I probably saw more tourists on the whole than actual people who lived in the city. The city is overrun with them. There was awhile where I was righteously disdainful (“I live here”), and then a while where I got used to them. Didn’t care, didn’t really see them. But when I was planning this road trip, one of my core principles was to see stuff in each city that tourists don’t typically see. To spend time with our charming hosts (Austin edition: Eli and Febianna) and ask them for places that were Off The Beaten Path.

I’m not a hipster (Rebecca snorts). I’m not too cool for The Beaten Path, just… well… I wanted to see “the real city” wherever I went. Again, I lived in New Orleans for three years; I know what the French Quarter looks like and what the rest of the city looks like, and I know they are not the same. So in each place I went, I wanted to take some time and see what made that city unique. What made Houston Houston or Austin Austin? What places or ideas could I experience to get a sense of that city’s soul?

Yeah, that lasted all of three cities.

It turns out that the places tourists typically visit are tourist attractions because they’re interesting! Who knew!

In two and a half days in Austin, we visited the Austin Science and Nature Center and hiked up a little trail with a creek and cliffs, went Texas two-step dancing at some bar White Horse to a live country band, did geeky trivia at another bar and met Rebecca’s cousin there (was that Wednesday??) and went to kareoke at a Korean place afterwards, walked through the Texas Capitol (that was just me, surprising everyone), ate Texas chili at a downtown place that had a sign ‘said “Hippies use the back door”, visited a clothing-optional beach at a beautiful man-made lake, took a yoga class…

Austin is a bad example. The only truly touristy things we did were the statehouse and the Science Center. (I really wanted to see the Congress Avenue Bridge bats, but we missed it–we were apparently in the middle of their birthing season anyway.) But like, you see? We missed the bats and the LBJ Presidential Library–which I didn’t quite feel right visiting without having finished The Path to Power and all its sequels, anyway–and Lady Bird Lake, and countless other known attractions.

That paragraph above was two days worth of stuff. Two days! It isn’t possible to see all the touristy-for-a-reason stuff, and see the off-the-Path stuff, and sleep, and eat, in a given city, on the timetable we have. Really, any timetable at all that isn’t Jack Kerouac’s. Cities are like wells. You can sink and sink and sink and still… never see all… that’s a terrible analogy. (This is a first-draft-to-post post because I need to go to sleep soon.) The point is that there’s more to see in any given town than I could possibly experience on a trip like this.

And that’s okay. The point of a road trip is the road. I’m not going to stay anywhere long enough to get a true sense of the place, because I’m a freaking tourist and that takes years to accomplish. I speak as someone who wanted/would still totally love to be a journalist, sports journalist, Congressional staffer, think tank guy, author, nonprofit manager, etc., all at the same time. I’m going to finish writing my book while I’m in graduate school. I don’t do well with picking and choosing stuff. But as a tourist, you have to. The world is too big to digest in one sitting.

Did I get a sense of the true soul of Austin? No. I have no idea what Austin is. Eli and Febianna and Rebecca’s other friends were cool. Vincente, the Portuguese skydiving life coach we met at White Horse, was a wonderful human being. So was Danny, Rebecca’s cousin. The dancers at the White Horse, the trivia people at the Spider, the people at Hippie Hollow, all seemed like interesting human beings who give the city color and who I’d love to get to know. And that’s all. Maybe I’ll come back someday; in fact, I’d love to come back someday, stay a week or two, and get a fuller sense of what this town is about. But that’ll have to wait. The road is calling first.

The Alamo and Texas Myths

In the Extra History series about Korea’s Admiral Yi, creator James Portnow spends much of his after-hours Lies episode talking about historical narratives. During his life, Admiral Yi is presented as an unfailingly noble and honorable person who persevered despite being betrayed time and again by unscrupulous nobles. His humbleness, willingness to work hard, and steadfast righteousness against all incentives are part of what make him Korea’s national hero.

Portnow talks about how this story is part history and part myth. Admiral Yi was that person, and he did do those things. But the reason he is celebrated for them in Korea, besides the fact that he won a war against Japan essentially by himself, is that he exemplifies the Confucian tradition of the humble, hard-working public servant. His story fits into and feeds an existing Korean historical narrative that those sorts of people are the righteous and prosperous ones, and which presumably forms a key part of Korea’s national identity.

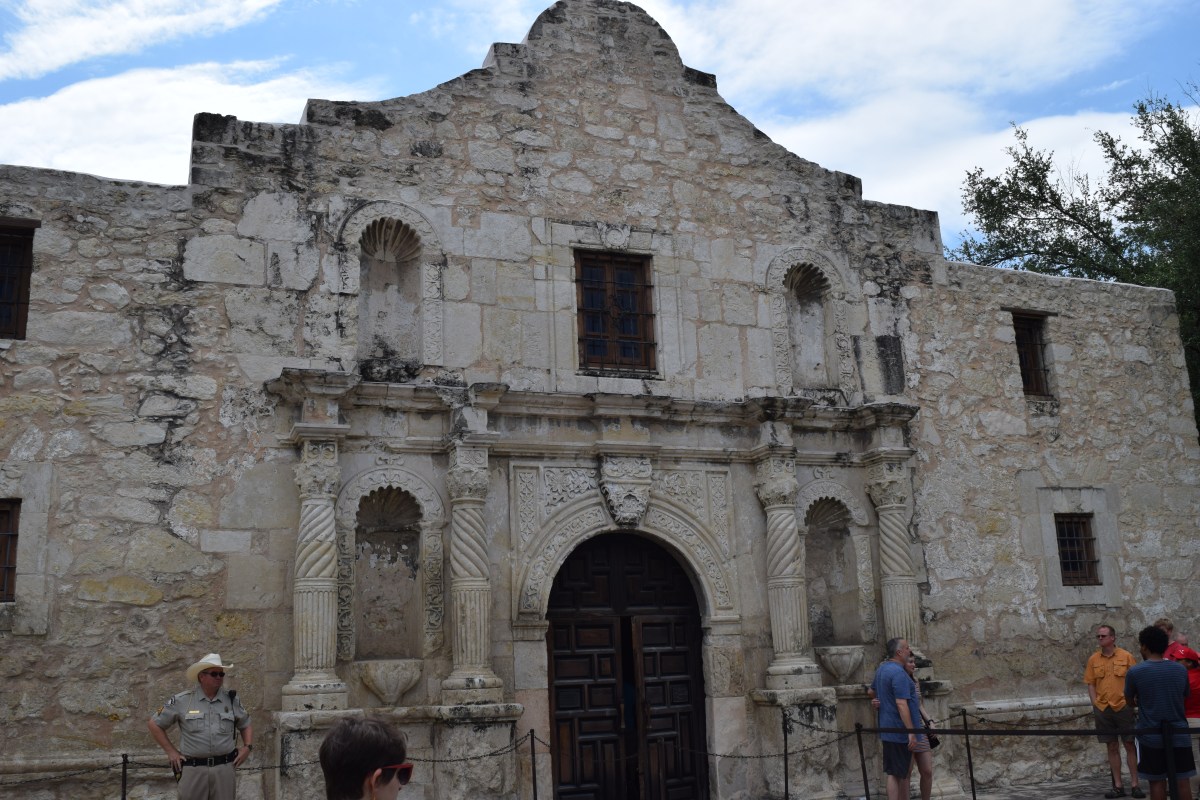

I was thinking about that when Rebecca and I visited the Alamo, located in San Antonio, Texas. I knew vaguely about the Alamo as the last stand of embattled, outnumbered Texans, but I had no idea how great an influence it has had on Texas’s conception of itself.

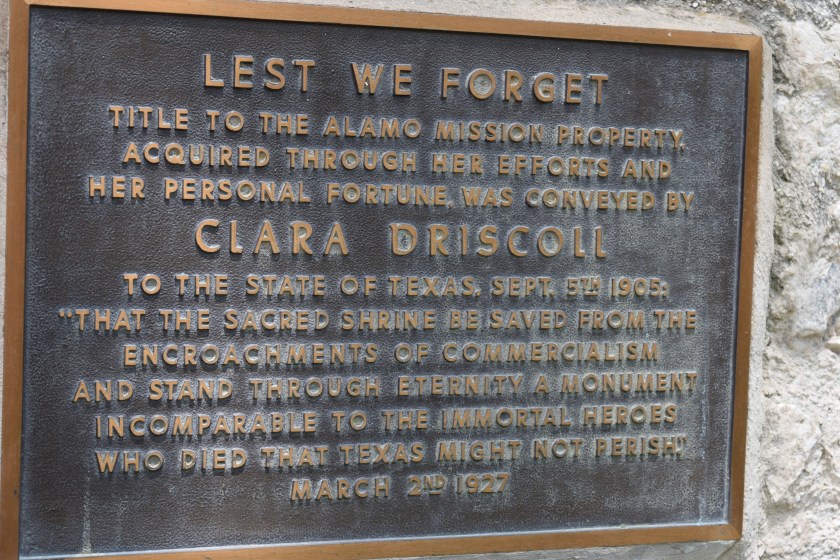

The video about the Alamo’s history, the signs outside and inside the Alamo (including the church where the lastest part of the last stand was made), and various other placards and inscriptions refer to the Alamo as a shrine, and to the battle or the Alamo itself as sacred. The statue in the courtyard outside the present Alamo, in an area once enclosed by the Alamo’s walls, contains a nude godlike figure, sheltering huddled figures at his feet, and a rather messianic inscription (would put a picture, but upload problems).

There is a real sense in the Alamo that this was not just any battle, or even any heroic last stand; the siege and storming of the Alamo was a foundational event in Texas’s history and Texas’s idea of who a Texan is and why Texas is special. The men who died on the walls, in the courtyard, in the barracks, and in the church are presented—in the film, the inscriptions, and so on—as freedom fighters, battling against an oppressive Mexican government that sought to curtail their power. The Alamo fighters are presented as ideal Texans: free men, hard-bitten and hard-biting, who are loyal and honorable and fiercely protective of their rights.

None of which is wrong out of hand. I would love to read more about the details of the Texian/Texan rebellion, why it happened (apparently General/President Santa Anna introduced a new centralized constitution that disempowered the various Mexican states, and a whole bunch of people rebelled) and what happened in it. The details of the Mexican secession from Spain, the Mexican governments and their policy towards encouraging Americans to settle in Texas, Santa Anna’s assumption of power, and of course the battles of the war itself are all lovingly detailed. But the narrative is a little too clean and fits a little too well into the narrative I know of what Texas is. In the Alamo’s telling, the American settlers are presented as basically blameless in Texas’s war for independence; they were encouraged to settle in Texas by generous Mexican land grants and comparatively expensive American ones—so much that they soon outnumbered native Mexicans 10 to 1—then appropriately rebelled when Santa Anna threw out the old Federalist constitution and replaced it with a Centralist one that would deprive them of their rights. It’s all neat, clean and tidy. There has to be more to the story than that.

The lack of eyewitnesses on the Texan side, other than a few women and children and one slave, has also led to what feels like myth-making to me. There are apparently multiple, conflicting eyewitness reports of Davey Crockett’s death, with at least one saying that he died fighting valiantly in battle, and another eyewitness saying that he was captured and executed. There are several accounts of James Bowie (pronounced “buoy”)’s death, which happened in his sickbed; he shot himself, he was carried out of the room by Mexican troops and killed, he was burned to death, he was bayoneted in his bed, or (as depicted in a painting shown in the video) he emptied his pistols at Mexican troops barging into the sickroom before being shot to death. And although fort commander William Travis died unambiguously—killed on the north wall—one story holds that Joe, his slave and the only adult Texan male to survive the battle, was released by the Mexican army and then traveled back to Alabama to inform Travis’s family of his death in person (which, bullshit).

I think all of that is part of the Texas founding myth. I don’t mean myth as in something that is automatically untrue, but myth meaning the stories that tell us who we are and about the world around us, where capturing how it feels is more important than exactly what happened and when. The Alamo was a touchstone for the whole identity of the state of Texas, because of it being a Last Stand and the “I would rather die than retreat”, the honorable frontiersmen who fought for freedom and would not be moved, the leaders who died like heroes. And the modern Alamo museum continues to celebrate that historical narrative, to correlate the story of the Alamo with the feeling of “this is what it means to be a Texan”. That doesn’t mean it’s right or wrong, just that it’s something to be aware of when we look at how people tell their own histories. (It’s also cool to see a state that has such a powerful and passionate founding myth as part of their identity; Wisconsin’s story is “We traded beaver furs… and then we started mining stuff”.)

Regardless, the Alamo was a really cool thing to see. I often have to make an effort to imagine, when I’m at a historical site or old battleground, that the peaceful, tourist-infested buildings or hills around me were once the site of a desperate struggle, fought by real men against men. They’ve made that connection pretty easy at the Alamo, including little touches that connect the events you’re reading about to the landscape around you, like the plaque that marks the wall where Travis was shot. They also tell the full story of the Alamo, from the Spanish missionaries that built the Alamo through the battle and the 170-plus years afterwards. There are lists of the dead in the church, swords and guns and lances in the old barracks, and mock uniforms of both sides. (Whose idea was it to put the Mexican troops in uniforms with white crosshairs on their chests?!) I walked out of there wanting to know more about the Alamo, the revolution, and the whole history of that time, which is really what any museum should try to accomplish.

Downtown San Antonio is also pretty neat, with a long Riverwalk crowded with restaurants that runs right through downtown, a Ripley’s Believe it or Not, kitschy tourist shops (it feels like they looked at the Alamo and went “WE ARE GOING TO MILK THIS FOR EVERY CENT IT’S WORTH”) and some really interesting shops; Rebecca bought a tiny wall-rug charm from a Turkish shop with beautiful glass lamps, and we both got a podiatry lesson from an elderly Indian cobbler when Rebecca asked him about the thread he was sewing with. True story.

Finally, I’d be remiss if I forgot to mention the hospitality of Jay and Leanne, whom we stayed with, and their two spoiled-rotten beagles, Max and Lady. We somehow both forgot to take pictures of them, but they exist—trust us. Leanne fed us the kinds of things that road people just shouldn’t be able to eat (chicken parmesan meatballs, poached pears, brownies and ice cream, homemade pizza, homemade cinnamon rolls) and dispensed a flood of helpful cooking tips, recipes, cookbook recommendations, and pitches for specialized kitchen equipment. (Apparently we need a KitchenAid blender and all of its accessories.)

I decidedly did not get this post up when I said I would last time. Instead of our first night in Austin, I’m putting this up on our first night in Santa Fe, having just finished a seven-hundred-mile drive across the desert of northwest Texas and eastern New Mexico, the part of the map that just looks brown. Another post will be forthcoming about the drive itself.